(This dharma talk was delivered on June 2, 2024)

Dear Dharma friends,

We have a toddler who is just over one. His current favorite book is Hello Sacred Life by Kim Krans. Because I read this board book upwards of four times a day, I can recite it by now:

Hello Sacred Sun

Hello Sacred Moon

Hello Sacred Earth

Hello Sacred Air

And so on. The book is boring and quite profound. As I cycled through the pages, I came to realize that the book is a bit like a doha, a song of realization. It speaks to something that Tibetan Buddhism talks about, which is sacred outlook. How can we welcome all of our emotions and experiences, our turbulence and our grief, as sacred?

Over the years I have heard my teacher Anam Thubten comment that perhaps, in the West, one of the things we are missing is this sense of the sacred. Maybe we don’t have enough sacred in our lives. We’re living within the brittle walls of capitalism. Even if we aren’t religious or spiritual, some of us sense the lack of something in this superhighway existence. There’s a texture missing. Call it tenderness.

The question becomes: What makes something sacred?

It’s probably what we give our attention to.

Last Thursday I went with friends on a pilgrimage to the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art in New York City. We took the Amtrak from Philly. The train was delayed. Hello, Sacred Delay.

I watched people spend the train ride up and back with their faces about four inches from their phones. When someone went to sleep, the phone was tucked under their arm, just as you would tuck your baby, quite near the heart. A number of people went to the bathroom on the train. They walked with their screens out, following the phone into the bathroom. Hello, Sacred Phone.

We went to the Rubin Museum because it’s closing on October 6th. I’m sad about this news. I consider the Rubin to be a living space. The art on the walls and in the cases is not dead art. The items are ritual objects to help us grow larger than our small selves trapped in ego. Through use of them we connect with our Buddha nature. This is the freedom of the dharma. Even non-dharma practitioners can feel the peace that is created in the Rubin.

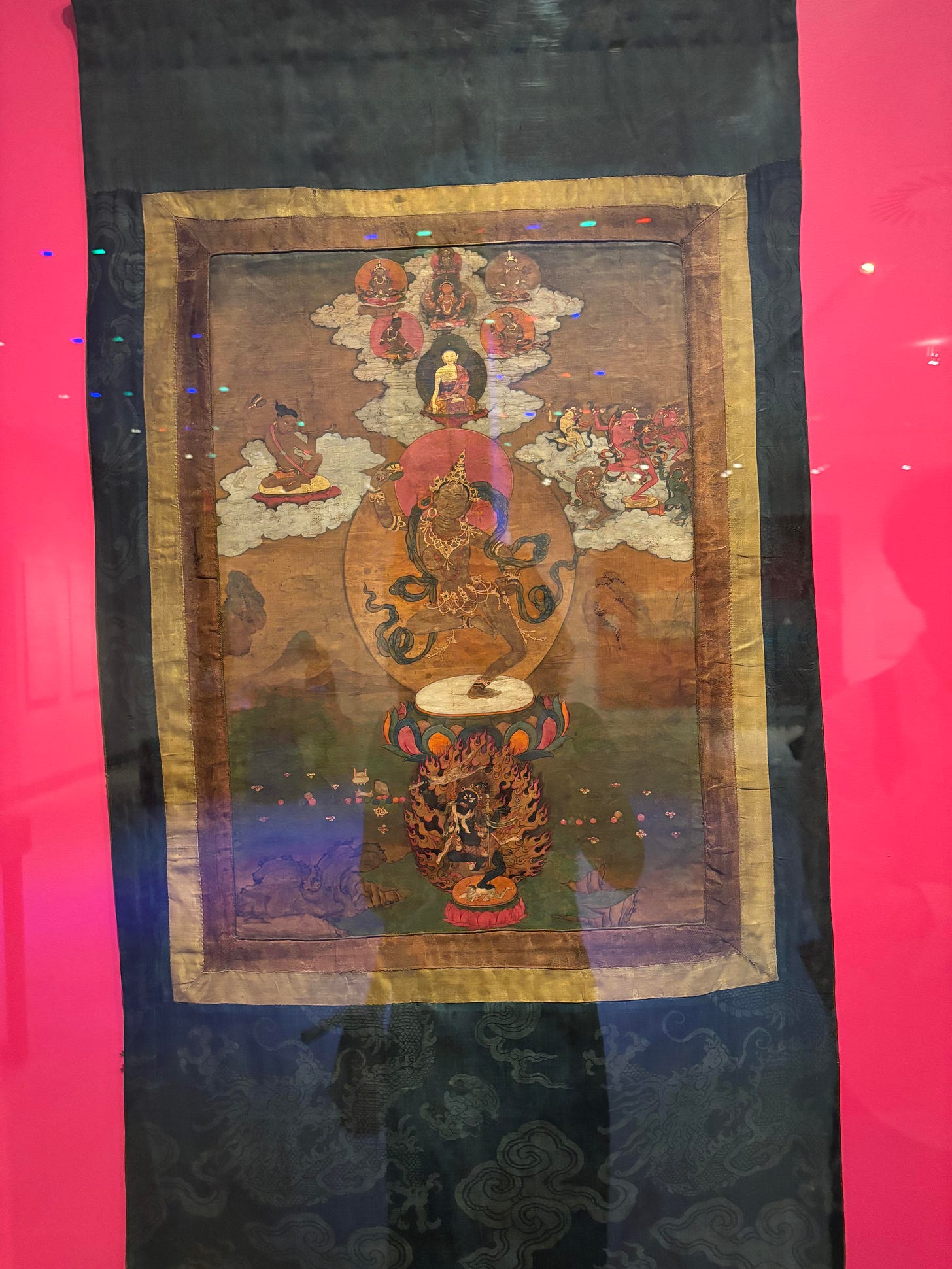

You go on pilgrimage to see something you consider sacred. For me, it was a thangka of Machig Lapdron that’s on display at the Rubin. Chod is the sadhana or practice that I do. It was originated by Machig Lapdron, a mother and mystic, in 11th century Tibet. There is nothing inherently sacred about an old painting of a naked woman dancing, playing a damaru, or drum, and bell. I do Chod multiple times a week. I feel it is opening up my insides, creating spaciousness and light. Because of my gratitude to Machig Lapdron for creating Chod, when I saw the thangka of her at the Rubin, I was flooded with excitement, awe, reverence. I was flooded with a sense of the sacred.

The middle floor of the museum has a mandala lab where you can work with your emotions, transmuting a poison into a wisdom. This is an old Tibetan Buddhist method that the Rubin is interpreting for anyone to try. Anger, for example, is represented in the lab by eight gongs made by different artists, suspended from the ceiling. There’s a huge tank underneath the gongs filled with water.

If you visit the Rubin before it becomes formless, I invite you to meditate as you circumambulate the gongs. You will know which one speaks to your anger. Pick up the corresponding mallet. Call your anger up. Summon a time when you could feel that hot energy running through your body. Give the gong a good whack. You’ll hear the sound of your anger. Then push a lever. The gong is dunked in water. Your anger is transforms.

Anger changes into what we call mirror-like wisdom. This is the sharp accurate information that anger can provide. It’s a quality that sees without distortion. In this way, we work with anger.

When I told my teacher Anam Thubten about my Rubin pilgrimage, he shared a story of a pilgrimage he went on when he was sixteen, to a statue of Avalokiteshvara on top of a mountain in Tibet. He said that through the act of pilgrimage, everything became sacred. Four days of walking, one day on a bus. The road was sacred. The villages. It gave him a new point of view.

Maybe we could ask ourselves what a pilgrimage would look like in our lives now. Perhaps there is an act we are already engaged in that could be transformed through sacred outlook. Perhaps it’s time to design a trip to a destination that you consider sacred. Try is as pilgrimage and note what happens. Can delays become peaceful? Mishaps? Accidents?

We could choose to regard our precious human life as pilgrimage and be deliberate about what we pay attention to on this journey.

With gratitude,

Sunisa